The POWER YOU need is INSIDE of YOU!

You cannot continue to allow yourself to be the victim, the power to overcome is inside of you!

No More Dropouts! That's Our Goal!

Every child needs to be encouraged by you. Every 26secs a child drops out of school. Click Here to Support Boostup!

HELP Sandy victims thru REDCROSS

Superstorm Sandy affected thousands in the Northeast, please make donations to assists our fellow Americans. CLICK HERE!

GET THE FACTS about, Bullying, Domestic Violence, and Race Relations

Here we've collected data to support our drive to do away with these three epidemics. Eventhough they may differ in one way, in many ways they cross and parrallel one another. Our goal is to catch it in it's incubator stage, but if by chance we miss it there, confront it at it's adolescent stage so that no further damage is done to the victims at hand.

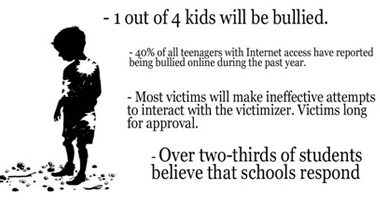

BULLYING

Statistics show that bullying is becoming a hugh problem. The prupose of this website is to assist the public on becoming aware of issues; such as school bullying, workplace bullying, and more. Our goal is to help teens, families, schools and the community -at large, get the education and assistance they need to prevent everyone from being bullied.

Bullying FAQ

My bully has made unwarranted criticisms/false allegations about me. How do I turn this to my advantage and reflect it back on the bully?

My HR people are insisting I use the grievance procedure, but the bully is my boss - what can I do?

The top four groups of people who contact the Advice Line and Bully Online are teachers, nurses, social workers, and those in the charity / voluntary sector. Why is this?

Can bullies be helped?

How can I find information quickly at Bully Online?

What can I do when my child is being bullied?

What are the different kinds of Bullies?

What happens to Victims?

Is name calling really bullying?

What are Common Characteristics of Bullying?

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Domestic Violence FAQ

My partner verbally abused or physically assaulted me. Can you help me?

I think my daughter/mother/friend/co-worker is a victim of abuse. How can I tell, and what can I do to help him or her?

I want to “speak out” against domestic violence. What can I do to support this cause?

Are men affected by domestic violence just as much as Women?

What is domestic violence?

What are resources available for victims?

Why do victims sometimes return to or stay with abusers?

Does abuser show any potential warning signs?

Is it possible for abusers to change?

How does the economy affect domestic violence?

Other Domestic Violence Facts

Because abuse

often happens behind closed doors, it is important to

understand the statistics that show just how many people

are affected.

·

1 in 4 women

report experiencing domestic violence in their

lifetimes.[1]

·

2 million

injuries and 1,300 deaths are caused each year as a

result of domestic violence.[2]

·

All cultural,

religious, socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds are

affected by domestic violence.[3]

·

Nearly 2.2 million people called local and

national domestic violence hotlines in 2004.[4]

·

More than 1.35

million people accessed domestic violence victim

services in 2005.[5]

·

The 2009

Allstate Foundation National Poll revealed

·

Over 75% of

Americans believe the recent economic downturn further

strained domestic violence victims and survivors.

·

67% of

Americans believe the poor economy has caused an

increase in domestic violence.[6]

National Impact

Domestic violence can be devastating to families, but its effect on

entire communities runs even deeper.

·

Over $5.8

billion each year is spent on health-related costs of

domestic violence.[7]

·

Nearly 8

million days of paid work each year is lost due to

domestic violence issues-the equivalent of more than

32,000 full-time jobs.[8]

·

96% of domestic

violence victims who are employed experience problems at

work due to abuse.[9]

·

33% of all

police time is spent responding to domestic disturbance

calls.[10]

·

57% of cities

cite domestic violence against women and children as the

top cause of homelessness.[11]

Domestic Violence & Gender

Domestic violence is an issue that does not discriminate - it can

impact people of all genders, races, incomes and ages.

But, the vast majority of victims of domestic violence

are women.

·

Survivors of

intimate partner violence are overwhelmingly female.

·

84% of spouse

abuse victims are women.

·

86% of victims

of abuse by a boyfriend or girlfriend are women. [12]

·

Intimate

partner violence against men is overwhelming committed

by male perpetrators.[13]

·

Nearly 5.3

million domestic violence incidents occur each year

among women in the U.S. ages 18 and older.[14]

Domestic Violence & Economic Abuse

Physical abuse is the type of domestic violence most commonly

discussed. But, economic abuse, using finances as

a tool of power and control, happens just as frequently.

·

74% of

Americans personally know someone who is or has been

abused.[15] However, 75% Americans also fail to

connect domestic violence with economic abuse.[16]

·

Approximately 6

out of 10 Americans strongly agree that the lack of

money and a steady income is often a challenge faced by

a survivor of domestic violence when leaving her/his

abuser.[17]

RACE RELATIONS

Race Relation FAQ

We would like to get funding for our anti-racism research project. How can the Foundation assist us?

We would like to get funding for our anti-racism project / initiative. How can the Foundation assist us?

Can you suggest information sources (books, readings, reports) about racism?

Can you suggest videos that we can use for our class presentation or community meeting?

Our organization is planning a conference (workshop, professional development day) on racism. Can the Foundation supply us with a speaker?

I would like information about federal government services (examples: immigration, taxation, agriculture, and veteran affairs) Where can I go for information?

I have a problem at my workplace or school related to racial discrimination. Can the Foundation provide me with assistance?

What can I do about hate crimes and hate incidents in my community?

Race Relations, in complex societies, such as that of the United States, involve patterns of behavior between members of large categories of human beings classified on the basis of similar observable physical traits, particularly skin color. Race is a social status that individuals occupy along with other statuses, such as ethnicity, occupation, religion, age, and sex. In the United States racial status has often been paramount, transcending all other symbols of status in human relations.

While it is virtually impossible to chronicle the history of American race relations in any single publication, this entry provides a brief glimpse at some of the events that played a major role in continually evolving relationships among America's various races.

Although there have been numerous instances of friendly and egalitarian relationships across racial lines in American history, the major pattern of race relations has been characterized by extreme dominant-subordinate relationships between whites and nonwhites. This relation-ship is seen in the control by whites of the major positions of policymaking in government, the existence of formal and informal rules restricting nonwhite membership in the most remunerative and prestigious occupations, the often forcible imposition of the culture of white Americans on nonwhites, the control by whites of the major positions and organizations in the economic sector, and the disproportionate membership of nonwhites in the lower-income categories. Race relations have also been characterized by extreme social distance between whites and nonwhites, as indicated by long-standing legal restrictions on racial intermarriage, racial restrictions in immigration laws, spatial segregation, the existence of racially homogeneous voluntary associations, extensive incidents of racially motivated conflict, and the presence of numerous forms of racial antipathy and stereotyping in literature, the press, and legal records. This pattern has varied by regions and in particular periods of time; it began diminishing in some measure after World War II.

The Twentieth Century

By the beginning of the twentieth century almost all nonwhites were in the lowest occupation and income categories in the United States and were attempting to accommodate themselves to this status within segregated areas—barrios, ghettoes, and reservations. The great majority of whites, including major educators and scientists, justified this condition on the grounds that nonwhites were biologically inferior to whites.

Although the period was largely characterized by the accommodation of nonwhites to subordination, a number of major incidents of racial conflict did occur: the mutiny and rioting of a number of African American soldiers in Houston, Texas, in 1917; African American–white conflict in twenty-five cities in the summer of 1919; and the destruction of white businesses in Harlem in New York City in 1935 and in Detroit in 1943. A major racist policy of the federal government was the forcible evacuation and internment of 110,000 Japanese living on the West Coast in 1942—a practice not utilized in Hawaii, and not utilized against Italians and German Americans.

Following World War II major changes occurred in the pattern of white dominance, segregation, and non-white accommodation that had been highly structured in the first half of the twentieth century. After the war a number of new nonwhite organizations were formed and, with the older organizations, sought changes in American race relations as varied as integration, sociocultural pluralism, and political independence. The government and the courts, largely reacting to the activities of these groups, ended the legality of segregation and discrimination in schools, public accommodations, the armed forces, housing, employment practices, eligibility for union member-ship, and marriage and voting laws. In addition, in March 1961 the federal government began a program of affirmative action in the hiring of minorities and committed itself to a policy of improving the economic basis of Indian reservations and, by 1969, promoting Indian self-determination within the reservation framework.

Although government efforts to enforce the new laws and court decisions were, at least at the outset, sporadic and inadequate, most overt forms of discrimination had been eliminated by the mid-1970s and racial minorities were becoming proportionally represented within the middle occupational and income levels. Changes in dominance and social distance were accompanied by white resistance at the local level, leading to considerable racial conflict in the postwar period. The Mississippi Summer Project to register African American voters in Lowndes County in 1965 resulted in the burning of 35 African American churches, 35 shootings, 30 bombings of buildings, 1,000 arrests, 80 beatings of African American and white workers, and 6 murders.

Between 1964 and 1968 there were 239 cases of hostile African American protest and outbursts in 215 cities. In 1972 Indian groups occupied Alcatraz, set up roadblocks in Washington, D.C., and occupied and damaged the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in that city. The Alianza movement of Chicanos in New Mexico in 1967 attempted to reclaim Rio Arriba County as an independent republic by storming the courthouse in Tierra Amarilla. Mexican American students walked out of high schools in Los Angeles in 1968, and a number of Chicano organizations boycotted the Coors Brewery in Colorado between 1968 and 1972. During the 1970s Chinese youth organizations in San Francisco, California, staged a protest and engaged in violence, claiming the right to armed self-defense against the police and the release of all Asians in American prisons.

The major developments in the 1970s were the increased efforts on the part of federal agencies to enforce the civil rights laws of the 1960s; a greater implementation of affirmative action programs, involving efforts to direct employers to take positive actions to redress employment imbalances (through the use of quotas in some cases); and the resistance in numerous communities to busing as a device to achieve racial integration in the public schools. In the 1970s America saw an influx of 4 million immigrants, followed by 6 million more in the 1980s. Millions more arrived in the country illegally. Most of the immigrants originated in Asia and Latin America and, by 1999, California, which was the nation's most populous state, had a makeup that included more than 50 percent nonwhites.

Hate crimes continued to grow from the early 1980s to 2002. In 1982 Vincent Chin, a Chinese American, was beaten to death in Detroit, Michigan, by two out-of-work autoworkers. The men blamed the Japanese for their lack of work and mistakenly believed that Chin was Japanese. In July 1989 a young African American man was assaulted in the mostly white area of Glendale, California. Despite these and numerous other instances of hate crimes throughout these decades, race relations became embedded in America's social conscience with the Rodney King beating. On 3 March 1992, a young African American man named Rodney King was pulled over for reckless driving in Los Angeles. Several police officers beat King, and despite the videotape of a bystander, an all-white jury acquitted the officers. Riots erupted in Los Angeles, resulting in 53 deaths, 4,000 injuries, 500 fires, and more than $1 billion in property damage. When speaking to reporters, King uttered what are now some of the more famous words surrounding race relations: "People, I just want to say, you know, can we all get along? Can we just get along?"

Bibliography

Kitano, Harry H. L. The Japanese Americans. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

Marden, Charles F., Gladys Meyer, and Madeline H. Engel. Minorities in American Society. 6th ed. New York: Harper-Collins, 1992.

Moore, Joan W., with Harry Pachon. Mexican Americans. 2d ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

Pinkney, Alphonso. Black Americans. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 2000.

Quarles, Benjamin. The Negro in the Making of America. 3d ed. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Sidbury, James. Ploughshares into Swords: Race, Rebellion, and Identity in Gabriel's Virginia, 1730–1810. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Simpson, George Eaton, and J. Milton Yinger. Racial and Culture Minorities: An Analysis of Prejudice and Discrimination. 5th ed. New York: Plenum Press, 1985.

Wax, Murray L. Indian Americans: Unity and Diversity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1971.

Read more: http://www.answers.com/topic/race-relations#ixzz2Atk0CjJD